Contracts Should Impart the Science of Agreement

Industrial firms often live (or die) by the long term agreements they make with others. Large, complex commercial agreements are the “currency” of trade for the majority of our B2B economy. This could be a year-long contract to supply a certain chemical to a plastics manufacturer, or an agreement by a pipeline to take a listed amount of natural gas from a producing field into a market hub. In such agreements there is a legal framework that applies, but just as important to our companies are the operational constraints and options that the contract dictates. It is the latter that I want to bring into view, as I have had the opportunity to witness several of these kinds of contracts coming together in recent years. What I have found in current practice was a primitive approach to contracts that stands in considerable contrast to the sophisticated tools we have today to improve operations. We can do better. I’d like to talk about how.

In one case of a chemical resins producer negotiating a 3-year “offtake” agreement with an auto parts manufacturer, I observed that the person in charge of securing that agreement pulled a spreadsheet template from a past similar agreement, changed a few numbers, then handed the spreadsheet to the other party for approval. A week later it was verbally approved and the terms were “sent over to legal” to complete the final document for all to sign. The revenue that was to flow through this agreement exceeded $500M. Is this how most industrial agreements are done? I suspect so, although I would like to think that a handful of forward-thinking business leaders see the obvious here. An incredibly complex product is made or service is performed and great technological power is brought alongside, while remarkably certain parts of that world are largely unchanged over the last half-century. Contractual agreements are a glaring example of this gap.

Contract Design

OK, we can do better. But how?

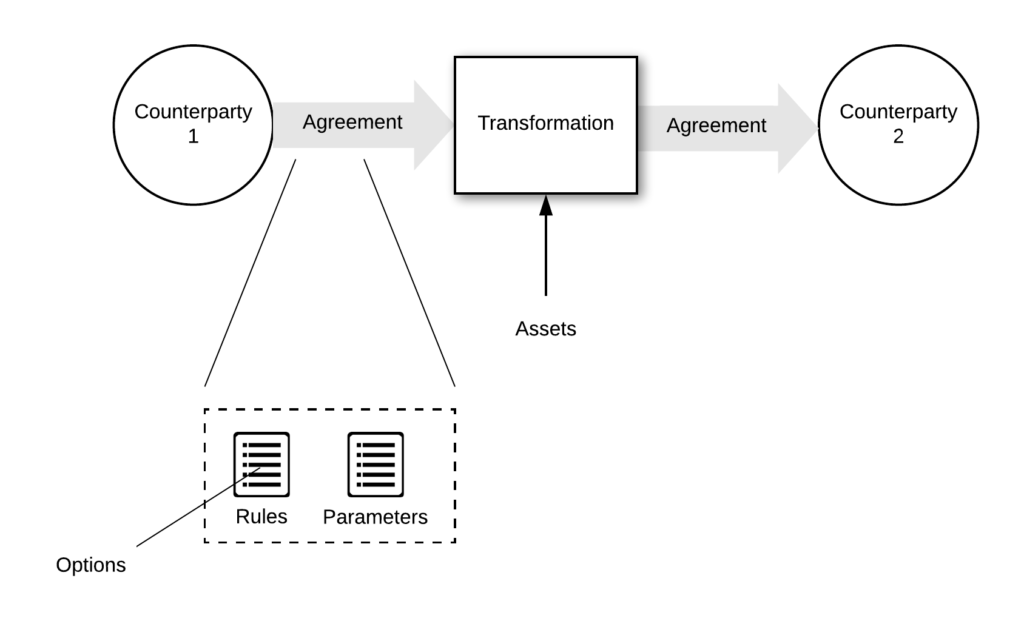

Let’s break down what a contract is in black box terms. In industrial settings, the core of a contract is a transformation using assets by the asset owner. This might be a pipeline that moves natural gas from the Permian Basin in Texas to Gulf Coast producers of polyethylene. The natural gas is “transformed” by its physical movement from the production location to the market location using a statewide pipeline network as the asset. A two-part agreement is executed, one between the pipeline and the shipper (the natural gas producer, likely an oil and gas operator), and the polyethylene plant owner.

Each agreement then consists of two primary structural parts: rules and parameters. Most often people talk about “Terms and Conditions” in this context, but here I refer to these as “rules”—the most basic molecule of an agreement that is also a word that allows us to segue into the algorithmic representation of a contract (more on that later). We can break down any agreement into its associated micro-rules, which can number in the hundreds or thousands. A rule might be expressed as follows:

“Party X agrees to ship 20,000 gallons of Y to party Z every month for 1 year”.

Now the parameters of the rules dictate type or scale. In the above example, 20,000 gallons and 1 year are parameters. I can alter those parameters back and forth independently of the structure of the rule. Therefore in designing contracts we have two domains to work with—rule structure and parameters. Putting these two domains together we refer to them collectively as “levers” on the contract, because the contract designer can manipulate these as the contract is negotiated among the parties.

Simulating the Contract

Simulating the Contract

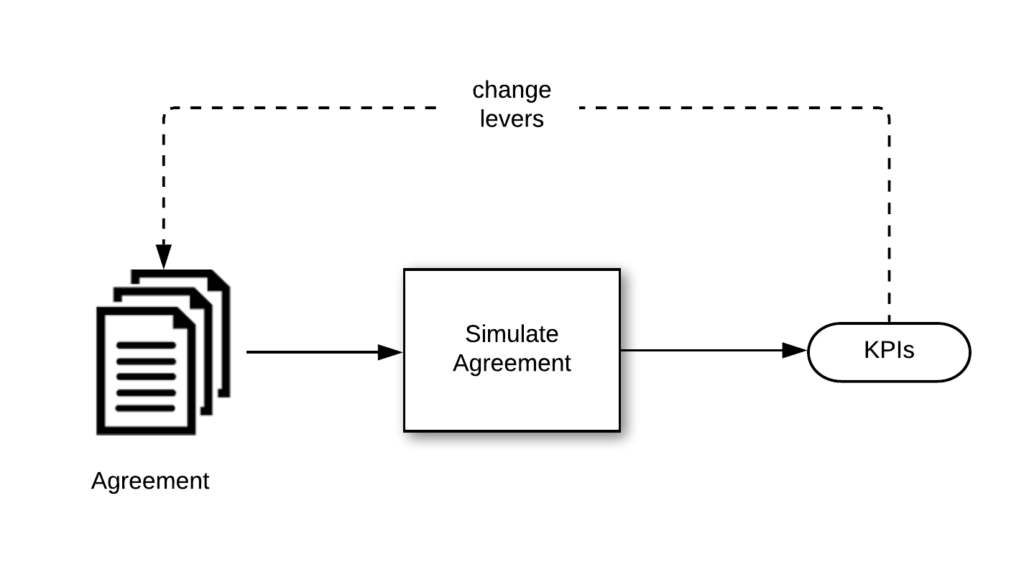

The new idea we want to raise here is simulation: simulating a “year in the life” of the agreement from an Operations perspective. This means putting all of the rules and parameters in software (not a spreadsheet) against the backdrop of Operations using its assets to effect the transformation.

The result of that simulation run is to show the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that result from that particular agreement design. The designer then returns to the levers, makes changes, and runs the simulation again, resulting in different values for the KPIs. This “what if” experimental design is part of a feedback loop that generally allows companies to seek an optimal contract design, one that is data-driven, objective, and methodical.

“But my spreadsheet can do that” is a common refrain that I hear. True, just as it is possible to ride a horse from New York to LA in lieu of more efficient means. Spreadsheets are simply inadequate for representing an agreement over time with deep operational complexities inherent in industry, while becoming unwieldy and error-prone as they bloat with an indiscriminate mishmash of data and logic. Spreadsheets were never designed for simulating complex systems over time.

Another use of the feedback loop here is in stress testing, a technique that is too seldom practiced today. By stress testing, we mean subjecting the agreement to unusual, exceptional conditions to see if the agreement accounts for that condition to the benefit of all in a graceful manner. The legal treatment of this is often Force Majeure, but these clauses rarely address the operational backup options available to us. Properly simulating the agreement would shine a light on the countermeasures we can bring to bear on exceptional circumstances we encounter in the real world.

The Role of Options in Contract Design

We mentioned the example of a simple rule previously. Most rules are “fixed” in this way. But there is another class of rules we should not ignore: contingent rules also referred to as options. An option might be declared in a contract as follows:

“If orders exceed X volume, the manufacturer has the right to extend the delivery window to the customer from 7 to 10 days”

Notice in this case the manufacturer is afforded additional flexibility contingent upon the condition of order volume. This is an option in the agreement that pertains to real-world conditions. For this reason, these kinds of options are referred to as Real Options. Because they closely mimic the same kinds of financial options traded on public exchanges—like calls and puts on stock issues—economists have figured out that a similar math that is used to value those securities can be applied in real-world cases like the example above. In other words, we can now put a precise financial value on the real world options in agreements. Creation of the Real Options methodology was a landmark step forward in the computational contract design movement, giving rise to “trading” back and forth a set of contingent clauses where the party that uses Real Options has the clear upper hand in knowing the precise value of each.

Game Theory

While you were busy running your business, economists were quietly thinking about the science of strategy. It came in the form of Game Theory, a body of knowledge about how competition works, and how coalitions are formed (competition and cooperation). The concept of added value entered the lexicon of negotiations where any given party’s received value is in proportion to the value they bring to the table.

Game Theory gives us all sorts of concepts and models to bring to the workshop when designing an agreement. From tactics like price signaling to strategies such as being “paid to play”, Game Theory represents a substantial set of levers to unearth and distribute value.

Gainsharing and Collaborative Design

Many times agreements are forged in an “I’m the buyer, you are the supplier” arms-length milieu. In other words, I as the buyer have complete power over you, lowly supplier, so I am going to use that power to extract all of the economic value of the transaction from you for myself.

I have no problem with players using their advantages in a fair economic fight. I do, however, disdain the short term thinking that does not actually lead to the creation of value in the long run for both parties. I know of several companies whose procurement departments actually have incentives to wind down pricing for purchased materials and services irrespective of the economics of that item. “You get a bonus if product A is $0.05 cheaper per unit this year versus last” reads the mantra. Win/lose is rarely sustainable.

I have also witnessed the arrival of a new “turnaround” CEO who did nothing for his company but string out suppliers from 30-day payment terms to 90 days, to the applause of shareholders.

These are examples of outdated, low-intellect, short term thinking.

These days the better companies that look beyond the next quarter are directing their energy toward something I call collaborative design: jointly working on company-to-company agreements that create more value. Why? Because often the customer’s own behavior places burdens and constraints on their suppliers that acts as a hidden tax that is passed back on to the supplier. By cutting through all of this and engaging in collaborative contract design, both parties benefit. Sustainable, stable agreements drive inherent benefits like learning curve effects.

But why would a supplier want to help its customer use less of the supplier’s product in cases where the customer’s inefficiency drives higher volumes? In conventional terms, it would not. However if there was something in place called a gainsharing agreement, any savings that are found between the two are shared equally. I recall working with an oil and gas company that hired marine vessels while executing a gainsharing agreement on the vessel fleet. After considerable work on the logistics system, 2 vessels were retired from that fleet, reducing the fleet cost to the customer by 25%. Not only did the vessel owner keep half of those savings, but he also re-deployed the 2 vessels in another market at better day rates. Everyone walked away happy, and more importantly, aligned for value.

Models can be handy references when designing joint supply chains and the agreements that cement them.

Blockchain and Smart Contracts

On the horizon, we see a role for blockchain in the agreement science domain. Blockchain provides a ledger system for storing the contracts as well as operational data that self-audits the performance of that contract in a secure, shared manner across multiple firms. But even more exciting is the prospect of using blockchain’s smart contract feature where self-executing contracts are embedded in code to automate many parts of the contract clauses.

What Industries Might Use The Science of Agreement?

Below is a partial list of industries where the application of agreement science is patently obvious.

- Engineering and Construction

- Midstream Oil and Gas

- Chemicals and Petrochemicals

- Asset-based service providers (like offshore drilling or oilfield services)

- Manufacturing

- Toll Processors

- Transportation of Materials (marine and land)

- Logistics and supply chain

- Utilities

- Commercial Real Estate

Summary

Contractual agreements are an often overlooked function in our Operational Excellence initiatives. Yet they are ground zero for tremendous value creation (or destruction). By applying scientific principles to the idea of designing an agreement among operational partners, we move closer to the ideal value creation for everyone, resulting in unsustainable relationships and long term gains.

Say yes … to the science of agreement!

About the Author

It’s no longer a question of intelligence; data is everywhere. “I have found that the common thread in the failure to get to a solution was not in the selection of the right technology or the application of the wrong math. It was trying to solve the wrong problem.” – George Danner.

George has 30+ years of experience in corporate strategy, specifically in operational and financial analysis, across a wide variety of industries: manufacturing, energy, telecommunications, transportation and financial services.

As Founder of Business Laboratory, George has his ear to the ground, filtering out fads from groundbreaking trends. Blockchain, artificial intelligence and automation is radically changing your industry’s landscape. Join us in the future of business.

For more information on George and how to reach out to him, visit www.georgedanner.com